Vermont Art Guide #2 Editorial

by Ric Kasini Kadour

In the second issue of Vermont Art Guide, Editor Ric Kasini Kadour asks the question, Is Vermont Art a Thing?

To get a copy of the editorial, purchase Vermont Art Guide #2 or subscribe.

In 1919, a group of Canadian men, all painters working in Toronto and organized by Lawren Harris, decided to form a group and devote themselves to making a distinct Canadian art. Fresh off of World War I and proud of their country’s contribution to the effort, this Group of Seven believed that the soul of Canadian painting was in the land and so they painted landscapes. Not to be outdone, in 1939, an artist in Montreal, John Lyman, brought together a group of artists who felt browbeaten by the conservative Canadian landscape tradition. They argued the soul of Canadian art was in the hearts and minds of the people and so they painted glorious abstract works and celebrated a radical, new Modernism. And then, not to be outdone, in 1973, a group of First Nation artists led by Odawa-Potawatomi artist (and living legend) Daphne Odjig were frustrated that they could only receive acknowledgement for their work if they pigeonholed themselves into narrow traditional formats. They formed the Indian Group of Seven and declared themselves leaders of Canadian art. Today, the question, What is Canadian Art?, is a lively conversation, debated in media and forums, considered when acquisitions are made and when exhibitions are presented. And each individual province asks this question of itself. What is Quebec Art? What is Manitoban Art? Etc. The result is a vibrant artistic landscape and an active dialogue between artists and their communities.

America doesn’t do this. America is the only country in the world that doesn’t ask itself this question. The United States is the only country in the world without its own art. I know that sounds strange, but hear me out. We can talk about art made in the United States. We can talk about 16th-century colonist John White’s watercolor sketches of the Algonkin peoples and the landscape of Roanoke Islands. Or we can talk about Joseph Badgers’ 18th century portraiture or the Hudson River School or American Impressionism or Southern folk art, and so on. But no art speaks holistically to the American consciousness. One of the reasons for this is that the America that we know today, the one, unified continental landscape did not exist until after World War II. For much of the nation’s history, states maintained unique and separate identities. And as time progressed, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the World Wars, the Civil Rights Movement, the Cold War, the consolidation of media into singular national entities, all of these things helped push the country to be “one nation under God”.

Perhaps there shouldn’t be an “American Art”. Our nation is diverse in ways one cannot imagine unless they have matured in the rust belt of Ohio, boated the bayous of Louisiana, or stepped out into a crisp autumn day in Vermont. But more than geography, art is always a product of the people who make it and those people are part of a dynamic community and all communities are local. To say that the desert paintings of Santa Fe breathe the same air as the seaside paintings of Maine is to deny each the complex communities that make each of those things possible, it denies the air that each need to exist and thrive. American Art too easily gets lost in the country’s own bigness, and a century of trying to force a narrow, urban idea of what American Art is hasn’t made Art better; it has isolated Art in a few elite pockets.

So let’s forgo the pretense and ask ourselves, Is Vermont Art a thing?

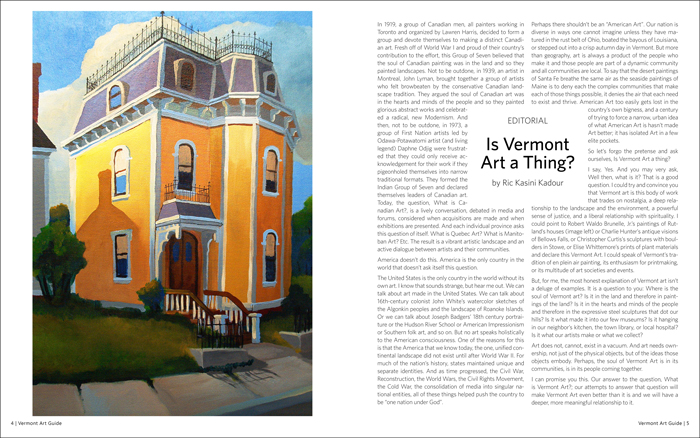

I say, Yes. And you may very ask, Well then, what is it? That is a good question. I could try and convince you that Vermont art is this body of work that trades on nostalgia, a deep relationship to the landscape and the environment, a powerful sense of justice, and a liberal relationship with spirituality. I could point to Robert Waldo Brunelle, Jr.’s paintings of Rutland’s houses (image above) or Charlie Hunter’s antique visions of Bellows Falls, or Christopher Curtis’s sculptures with boulders in Stowe, or Elise Whittemore’s prints of plant materials and declare this Vermont Art. I could speak of Vermont’s tradition of en plein air painting, its enthusiasm for printmaking, or its multitude of art societies and events.

But, for me, the most honest explanation of Vermont art isn’t a deluge of examples. It is a question to you: Where is the soul of Vermont art? Is it in the land and therefore in paintings of the land? Is it in the hearts and minds of the people and therefore in the expressive steel sculptures that dot our hills? Is it what made it into our few museums? Is it hanging in our neighbor’s kitchen, the town library, or local hospital? Is it what our artists make or what we collect?

To get a copy of the editorial, purchase Vermont Art Guide #2 or subscribe.

Image:

Gold House

by Robert Waldo Brunelle, Jr.

26″x18″

acrylic on canvas